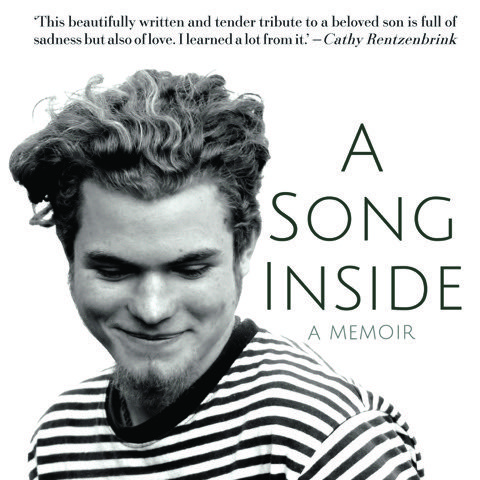

When Gill Mann, mother of Sam and author of ‘A Song Inside’, offered to write an article for SLOW we leapt at the chance.

Meeting Gill feels a bit like ‘knowing’ someone without knowing them very well at all. The recognition between parents who know the pain of losing a child needs few words, it is felt in the bones. And yet, Gill writes so beautifully about the life and death of her son Sam, the heart-break, the universal themes of parents’ grief, the senseless chaos, the world shattered, the intense beauty in nature, and the glimmers of hope. As a psychotherapist too she shines a light on the path that all bereaved parents must tread, each in our own unique way.

A Song Inside tells the story of Gill Mann’s son, Sam, who died when he was twenty-two years old and away travelling in Thailand. It also tells her story, which unfolds in journal entries that span the two years following Sam’s death. Gill writes as a mother about her grief and its impact on her life and family. But she also writes as a psychotherapist, drawing on her professional knowledge to understand her own and others’ responses to her loss. She has agreed to share some extracts from her book with us, together with some reflections on them.

Please visit Gill’s website for more details of the book and a beautifully poignant film of Sam.

____________________________________________________________

The changing landscape of grief

When Sam died I didn’t know whether I would survive it, whether I would ever find a way to re-engage with life again. It seemed unthinkable that my identity could ever be anything other than that of a mother who had lost a child. And if I’m honest, I didn’t want it to be. I didn’t want to imagine a life beyond my grief. To have done so would have felt like an enormous betrayal of Sam.

It feels a little different now, six and a half years down the line. I’ve learned many things in that time: some that surprise me and some that merely confirm things I suspected to be true. Most importantly, I’ve discovered that although I’ve lost Sam as a physical presence in my life, he is very much alive for me – a frequent presence in my thoughts and in the life of my family. As time has passed, the quality of his presence has changed, shifting from a source of overwhelming pain, to one of solace. My sadness at his death will never diminish but I can think of him now with gratitude too.

We each have to find our own way through loss and grief but I hope that anyone reading these extracts might discover in them things that resonate with their own experiences.

My book opens in May 2014, with a knock on the door:

At the garden table, mug of tea in hand, I sit and wait for the young policewoman to speak. It is Bank Holiday Monday: a day of bright sunshine and impossible clarity. Colours around me shout and sing. Blood-red geraniums in terracotta pots, fresh-cut grass as green as newly minted peas, wisteria hanging in swathes of smoky mauve.

‘You have a son,’ she says, placing one hand on the swell of her unborn child. It is such a simple statement of fact, a lovely truth, but a strange one for this young woman to be telling me, sitting in my own garden beneath a sky of cobalt blue. It seems she doesn’t expect an answer for she is carrying on, but ‘Yes,’ I agree in my head, ‘I have.’ She tells me his name too.

‘Samuel Edward Roberts,’ she says.

‘Yes,’ I agree in my head, again. …

More words come… I feel a sudden, cool waft of foreboding, as fleeting as the shadow of an aeroplane passing before the sun. Then a strange thing happens. The words cease to belong to the young woman opposite me. They take on an embodiment all of their own. I can see and feel them, floating on the garden air.

‘He’s travelling in Thailand, in Mae Hong Son province,’ her words continue, relentless. Suspending themselves in the space between us, above the table, they hang in the air like an executioner’s axe.

There is no faltering, no change of pace or tone when she speaks again. ‘Your son has been found dead in his hotel room. We’ve been contacted by the Thai police.’

There is silence as the words sway in front of me. Such an innocent conglomeration of consonants and vowels; but put together, such devastating words. Words which must not be allowed to turn that simple, lovely truth, ‘You have a son,’ into a terrible lie.

Everything becomes still and intense: the geraniums, the freshly mown lawn, the bird song, all freeze for a moment.

This woman is telling me my son’s life is over. She’s sitting there with a hand resting on her future while, in one sentence, she takes mine away from me. I want the sky to dim and the birds to fall silent. I want leaves to wither and fall to the ground. I want the world to acknowledge that everything has changed. Forever.

But nothing happens. The earth proceeds on its slow revolution round the sun. The garden all around me swells with new life; bluebells unfurling in the long grass, wisteria in every shade of purple, the magnolia tree slowly opening its petals, tongues of white velvet shot with pink.

The question at the heart of every parent’s grieving

Any parent who faces the death of a child will have their own tragic moments seared into their minds with a terrible intensity. The circumstances of each death will vary and people’s responses to it too, but despite the differences I suspect that – in the long hours and days and weeks and months that follow a child’s death – every parent will share one particular need: to try to understand something that simply doesn’t make sense, that they are still alive when their child is not. Over and over again we ask ourselves, ‘How can this be?’

For a long time it is almost impossible fully to take in that a child has died. Sometimes it seems that we can know it cognitively without entirely knowing it emotionally: almost as though it’s too huge an upset to the natural order of things for our minds to absorb it and retain the knowledge of it.

I still forget sometimes that he is dead. It happened yesterday. I felt myself falter psychically as I remembered. I had to give myself a moment to re-calibrate my world once again.

Bearing the unbearable in order to stay connected

Writing became a way for me to try to make meaning of Sam’s life and death. I didn’t set out to write; it simply happened. At four o’clock one morning, unable to sleep – and just thirty-six hours after I’d stood in a Buddhist temple in Bangkok and watched four young men slip out of the shadows to manhandle Sam’s coffin into a giant oven – I found myself sitting up in bed, reaching for my iPad and starting to write. And once I’d started I couldn’t stop. For the next two years I sat and tapped away whenever and wherever I could and what emerged was part journal, part exploration of the past, but also a conversation. I discovered that I was talking to Sam and that I needed to. I had so much to make sense of.

I can see now that writing fulfilled different functions for me at different points in my grieving. Initially, that instinctive urge to write was an unconscious prompt to help me understand the reality that seemed determined in those early day to evade me; the reality that Sam was dead. But once his death felt more real to me, it changed a little. Writing became my way to process and make sense of even the most painful of memories and feelings; a way for me to face the pain of loss head on. It’s natural to want to avoid pain and often we find ourselves doing exactly that without even realising it, but my training and clinical experience told me that if I could bear to face and feel the pain, in time this would help me to reconnect with Sam and, when I was ready to, to re-engage with life. And it did.

Ultimately writing became a way for me to spend time with Sam, to check out of daily life for a while and be with him. It’s important to spend time with the children who are no longer physically present in our lives. We each have to find our own way to do this and make the time and space for it, but if we can bear the discomfort of the pain, in time these acts of feeling and processing have the capacity to release gifts too – memories that make you smile and feel grateful for the life of your child.

As time went on I discovered small ways to connect with Sam: buying his favourite foods, going to places he’d loved, thinking of him as I went about my daily life. I didn’t always do this consciously, but sometimes allowing myself simply to follow an instinct in a particular moment, brought me comfort. One day, out on a walk in the hills of Wales, we came across an unusual place:

There is a tiny church in Partrishow and little else. It’s the Church of St Issui, founded in 1060 with the offerings of pilgrims to an early Welsh saint who lived close by. It clings to the hillside, its ancient gravestones leaning into the valley below, bending low to protect themselves from the wind and swirling cloud. There’s rain in the air as we walk around the churchyard. Some of the headstones bear only the faintest traces of the words once engraved into them. They wear coats of lichen in soft silver-green.

I try the door. It opens and we step inside. There is a timeless simplicity to this patient, weather-worn place – an echo of pilgrim feet, of prayers intoned in quiet supplication, of new lives celebrated and lost lives mourned. On the wall is a plaque for a seventeen-year-old son: “He giveth His beloved sleep.”

We find that the rain has passed when we step outside again. A wash of weak winter sunshine now bathes the church’s grey, stone walls and steep-pitched slate roof. We make our way down to the well where a huge flat stone marks the grave of St Issui. It is a place of healing and pilgrimage still. All around are small offerings: teetering pyramids of pinecones and pebble cairns. The trees by the side of the stream, the Nant Mair, are hung with strips of cloth and dotted with hammered coins. I feel a pressing need to leave something of Sam here too. Back at the car, in the boot, I find a single black sock with a name-tape stitched in green: Samuel E Roberts. I tie it to a low branch. It takes a while to get the name-tape to face outwards. It seems to matter that it does.

Managing disappointment and other difficult feelings

Most bereaved parents will have been disappointed at times by others’ responses to their loss – those who simply don’t know what to say and therefore say nothing or those who say unhelpful things, like a woman who told a mother whose son had recently died, that she’d heard all about her ‘dramas.’ But the challenges of negotiating grief go beyond this too. Sometimes it isn’t anything that someone has done or not done that upsets us, it is simply the difficulty of finding our place in a world where others still have their children. It’s hard not to feel envious of other lives and families untouched by tragedy.

Grief is multi-layered and often confusing, because it isn’t just about sadness, but about other feelings too, like anger and envy. It’s hard to know what to do with these uncomfortable feelings. Do we try to suppress them altogether or do we allow them an unfettered run? In my experience, both these extremes risk shaping our lives in a negative way. If we deny ourselves such feelings we’re more likely to act them out unconsciously, often without even realising it. If we simply act on them without thinking them through, we might discover too late that we’ve cut ourselves off from people who matter to us, simply because of the pain of being around them and their still-complete families.

There is another way to manage these difficult – but entirely natural – feelings. If we can make space for them internally, acknowledge them to ourselves, and then work through them, recognising the pain that lies behind them, we give ourselves the opportunity to make choices that are likely to serve us better in the future. The next three extracts touch on this.

As I make my way to the churchyard to see Sam, I look back across Mill Green to the three women I’ve just said goodbye to after an early morning walk: sensitive, warm, supportive friends. I feel all of a sudden very alone on my way to see my dead son, as they head home to carry on with the lives in which their sons still play a part.

Envy is an ugly feeling. I’m aware of it jostling for space, elbowing its way in when I see or hear of Sam’s contemporaries reaching milestones he will never now reach. I try not to let it take too much of a hold. I know that the momentary satisfaction of an envious comment or act dissipates all too quickly. There’s nothing to sustain me in the hollowness that follows. I know too that I mustn’t suppress it altogether. I let myself acknowledge its presence and its legitimacy. How could I not envy my friends and family for their happy fortune of having all their children still? I try not to hate them for it but if I do, just for a moment, that is alright.

***

In the supermarket, I meet a woman whose son who went through ten years of school in the same class as Sam. We stop for a quick chat. We re-meet in almost every aisle. She makes no mention of him, not in the first aisle, nor the second, nor the third, nor the fourth. Finally, between the tonic water and the crisps, I bring him into the conversation, mentioning a mutual friend who came to his funeral. Still she utters no words of sadness, no condolences as a mother, no simple, ‘I’m so sorry.’ Instead she stutters that she didn’t come because she, ‘didn’t really know him.’ In my world of loss this feels irrelevant. She’s missing the point. You come out of shared humanity. You come because it could have been you. It could have been your child.

It’s hard not to blame people for their inadequacy in the face of death, however unfair that is. I have a mental hate-list of all the people who ‘should’ have come to his funeral but didn’t; who have failed to mention his dying; who don’t pick up my cue when I say his name. I need somewhere to locate my anger about the unfairness of his death. I feel a perverse thrill of pleasure when I add a name to the list.

And despite understanding that people who avoided Sam’s funeral or said nothing were simply protecting themselves from the thought of pain so intense that they doubted their own ability to cope with it – I still need someone or something to blame.

My hate-list provides a focus for all my difficult feelings.

***

I think of the things people say, intending to help: “don’t let yourself get too down,” and “perhaps you’re spending too much time thinking about Sam,” or “give me a call and we can go out and do something nice.” It feels as though they’re telling me not to grieve. I ignore them. They aren’t me. I’m grieving my way. It’s the only way I know.

Managing the loneliness of grief and working through pain

I felt lonely after Sam died – not just around friends and acquaintances, but even around close family. I soon realised that though our loss of Sam was shared, our individual experience of it and our ways of dealing with it were different. It shouldn’t have surprised me, but it did.

It surprised me too how often – despite the apparent confidence with which I wrote, ‘I’m grieving my way’ – I questioned myself about whether I was grieving the right way. The next two extracts come later in my book and at a time when I was beginning to understand grief better and to accept its vagaries.

Grief is exhausting. And complex. And confusing. It’s so hard to know if one is doing okay. There are no pointers, no rules, no markers to tell you if you’re on the right path. I have no idea whether I am or not. But I begin to realise more and more that in many ways it doesn’t matter. I am simply where I am.

***

Even when loss is shared, grief is a solitary process. [We] are each engaged in our own journey. We respond to different triggers, find different meanings, experience different moments of calm or storm. We’re powerless to do anything other than plod along grief’s path in our own time, at our own pace and in our own way. It would be much less lonely if there were a choreographer on hand to oversee the whole; to ensure matching descents and ascents, to create a harmony of pain or hope, rather than the clashing reality of difference.

You can’t chart grief’s course, nor predict its length, nor set the moment where one stage will pass into the next. It isn’t a linear process, but a constant moving backwards and forwards and backwards again. We can manipulate it to some degree, as I do, with my conscious decisions not to ‘go there’ on my working days when I need to focus on clients; and on the days that I open myself up to its raw power by listening to music or Sam’s voice. But it’s largely its own master, neither to be hurried nor slowed.

For me it also seems to have developed an inverse reality. In the very early days and weeks the good days were those when I could function without being overwhelmed, and the bad days were those when I could think of nothing other than Sam and my loss. But now I think of the ‘bad’ days as ‘good’ days and vice versa. The ‘bad’ days help me move forward with my grief, whereas the ‘good’ days fail to.

Perhaps the real difference between then and now is that now I can think and process. Then it was all I could do to survive.

Here again I refer to my belief that it is through allowing ourselves to feel the pain of loss and think about our feelings that we find a way through. My clinical work as a psychotherapist has shown me time and time again that avoiding the pain of loss by keeping oneself busy and distracted rarely works in the long run. At some point pain will out and – either emotionally or physically – make itself felt.

The potency of anniversaries

The anniversary of a child’s death is enormously painful. The memories come crowding in and throw into sharp focus all that has been lost. Any bereaved parent will be aware of things that trigger feelings in them at certain times of year. Sam died in early May and here I describe the lead-up to the second anniversary.

My mind and body know it’s that time of year again. It’s the light, the colours, the scents, the sounds that link me to that moment of learning Sam was dead. It’s part of my DNA now. I see the smoky mauves of the wisteria hanging outside my bedroom window, the droop of laden blooms pulling down the twisted branches, blossom falling like silent rain from the cherry tree, the oak tree yielding up its sticky clusters in neon green as the squirrels tear from branch to branch. I hear the insistent tap-tapping on the window as a long-tailed tit, confused, tries to gain entry. I smell the faint perfume of damp bluebells rising up as I walk through the woods. It’s as though these things are all imprinted on a psychic retina that matches shapes and colours, sounds and scents and fits them into some sort of jigsaw of past experiences.

I feel the melancholy before I remember why.

The paradox of loss and gain

The loss of Sam will always be a huge part of me, but I can see now – six and a half years on – that it isn’t the only thing that makes me who I am. We are all, inescapably, shaped by the things that happen to us. But we don’t have to be defined by them. It is what we do with them, that makes us who we are.

In early grieving we find ourselves in a place of overwhelming pain, where there simply is no space for anything other than feeling. We need to feel, it’s a vital part of grieving. But in time we need also to think about what we’re feeling, to make those feelings conscious. It is through reflecting and processing that we discover we have choices: not over what we feel – we can’t help that – but about what we do with our feelings; how we react to them or act on them.

It is by thinking consciously about our loss and all the difficult feelings engendered in us, that we find ourselves moving on from that very first question, ‘How can this be?’ to a different question: ‘How do I want to respond to this?’ It is slow, hard work to find answers, but it pays dividends in the long run if we can at least try to. It helps us to manage better the pain of our child’s death, to negotiate a world that continues to turn despite our loss and perhaps most importantly of all, it allows us to choose whether to be open to the possibility of healing and gain. In the words attributed to psychiatrist and holocaust survivor, Viktor Frankl, ‘Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.’

This final extract reflects something of this, of the need to acknowledge and feel our pain whilst also allowing good things to reach us.

The flowers are wilting on Sam’s grave when I visit. The gerberas with their hanging heads, and the sun-charred leaves of the alstroemerias fill me with sudden hopelessness. I think of the sunshine of the last few days and how I enjoyed the feeling of warmth on my skin, felt nourished and restored by it. And all the while it had been destroying the flowers I had lovingly put there for him.

It seems profoundly depressing that gain must always walk hand in hand with loss, that love and joy come only with the risk of pain, that though life gives, it also takes away. The world seems all of a sudden to be a place of bleakness. All day this bleakness stays with me. I can barely bring myself to look at photos of him. I cannot bear the waste, the unfairness and the pain.

Paddy is away. I let myself stay with the lowness of my mood. I do not try to lift myself out of it. I wait instead for it to pass.

It does. Out walking I see buttercups, their bright glazed petals like bursts of sunshine in the hedgerow; lacy heads of cow parsley, their white florets like tumbling snowflakes, captured and frozen mid-flight onto green fronds. In the lake, the oily black head of a cormorant protrudes above the water, rises up and dives. Around the point of entry ripples fan out in circles, ever reducing, until the water is calm again. I stop to watch and wait, and wait, until some metres away he re-surfaces beak first, like a missile breaking the water, shaking the water droplets from his glistening feathers.

And I realise that though life takes away it also continues to give, if only we can allow it to.